This step provides guidance on how to create a draft results map using what is commonly referred to as a ‘results mapping technique’. Developing the draft results map can be time-

consuming but is extremely worthwhile. The fundamental question that stakeholders in the planning session should answer is “What must be in place for us to achieve the vision and objectives that we have developed in the particular problem area?”

Creating a set of positive results

A good starting point in creating a results map is to take each major problem identified on the trunk of the problem tree and reword it as the immediate positive result with longer-term positive results or effects. For example, if the problem were stated as “low public confidence and involvement in governance” the immediate positive result could be “greater public confidence and involvement in governance.” This could lead to longer term positive results such as “wider citizen participation in elections, particularly by women, indigenous and marginalized populations” and “greater compliance with public policies, particularly taxation policies.”

Likewise, a challenge of “low levels of public confidence and involvement in electoral systems and processes, particularly among women, indigenous and other marginalized groups” could be translated into a positive result such as “greater public confidence and involvement in the electoral process, particularly by women, indigenous and other marginalized groups” leading to “higher levels of citizen participation in elections, particularly by women, indigenous and marginalized populations.”

Results should be stated as clearly and concretely as possible. The group should refer back to its vision statement and see if there are additional long-term effects that are desired. These longer term effects should look like a positive rewording of the ‘effects’ identified on the problem tree. They should also be similar to, or form part of, the broader vision statement already developed.

Note that the first or immediate positive result, that is, the result derived from restating the major problem identified on the trunk of the problem tree, is the main result that the stakeholders will focus on.

With this immediate positive result, stakeholders should be able to prepare the map of results. A results map (sometimes referred to as a results tree) is essentially the reverse of the problem tree. In some planning exercises, stakeholders create this results map by continuing to reword each problem, cause and effect on the problem tree as a positive result. While this approach works, a more recommended approach involves asking the stakeholders “What must be in place for us to achieve the positive result we have identified?” When groups start with this approach, the process is often more enriching and brings new ideas to the table.

A key principle for developing the results map is working backwards from the positive result. Stakeholders should begin with the positive result identified in the step before. This is the statement that sets out what the situation should be once the main problem on the trunk of the tree is solved. The aim is then to map the complete set of lower level results (or conditions or prerequisites) that must be in place before this result can be realized. These are the main tasks for this exercise:

1. Stakeholders should write down both the immediate positive result and all the longer term results of effects that they are trying to achieve. Going back to our example, this positive result could be “greater public confidence and involvement in governance.”

2. Stakeholders should then work backwards and document the major prerequisites and changes needed for this result. For example, using the result above, stakeholders might indicate that in order to achieve this, the country may need to have “greater public confidence in the electoral process and in government,” “increased awareness among the population, and particularly by women and indigenous populations, of their democratic rights and of the responsibilities of the state,” “improved capacity of the state electoral machinery to administer elections in a free and fair manner,” “changes to government policy to make it easier for women and indigenous groups to exercise their democratic rights,” “greater acceptance, tolerance and respect for minorities and indigenous populations,” and so forth. Stakeholders should compare these conditions and prerequisites with the set of underlying causes identified on the problem tree. The conditions should read like a solution to those causes or should be closely related to them. Note that while they should be closely related, they may not always be the same.

3. Next, stakeholders should document other lower level prerequisites that are needed for the first set of changes and conditions to be in place. For example, in order to have “improved capacity of the state electoral machinery to administer elections” there may need to be “bi-partisan consensus between the major political parties to improve electoral laws and the administration of the electoral system.” These lower level results should be closely related to the lower level causes identified on the problem tree.

4. Stakeholders should note that these prerequisites are not actions that any one group of stakeholders need to take, but rather the set of key things that must be in place. The question should be phrased as “If the country were successful in achieving this positive result we have identified, what would we see happening in the country or on the ground?”, not “What should be done by UNDP or the government?”

5. Once the various prerequisite intermediate changes have been identified, stakeholders should then identify the interventions that are necessary to achieve them. At this point, only general interventions are necessary, not their implementation details. For example, “bi-partisan consensus on the need for reform of electoral laws and systems” may require “training and awareness programme for key parliamentarians on global practices and trends in electoral reform and administration” or “major advocacy programme aimed at fostering bi-partisan consensus.” Likewise, a result relating to increased awareness of women, indigenous populations and other marginalized groups may require a mass-media communication programme, an advocacy initiative targeted at specific stakeholders, and so forth.

6. Throughout the process, stakeholders should think critically about specific interventions that may be needed to address the different needs of men, women and marginalized groups.

Stakeholders should be aware that the results map may need more thought and narrative documentation over time. In addition, the results map may change as stakeholders gain new information or more understanding about how the programme works or as they begin the implementation process. Therefore, the group should be open to revisiting and revising the map.

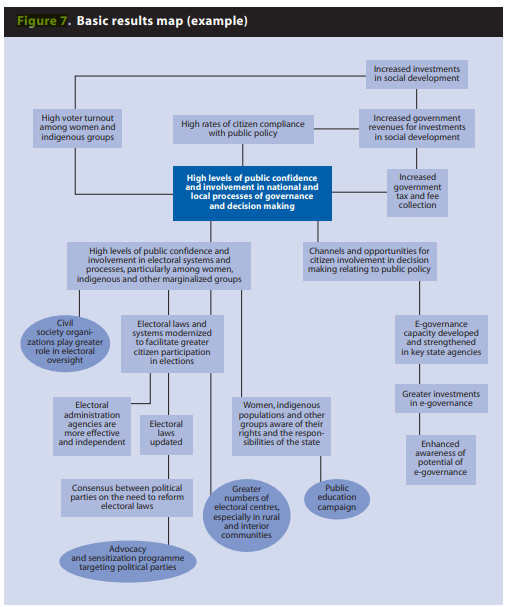

These maps initially avoid the traditional input-to-output-to-outcome linear tables, which tend to confine discussion to an agency’s specific outputs. In this model, the process focuses on all the things that need to be in place, irrespective of who needs to produce them. Returning to our example, a basic results map may look like Figure 7.

In this example, stakeholders have begun to identify additional ‘things’ that must be in place (oval-shaped boxes), some of which could be developed as projects.

TIP

effort should be made not to label them as such at this stage of the exercise. If labeled as outputs or projects, the tendency will be to concentrate discussions on which agency or partner can produce the outputs, rather than on what needs to be in place, irrespective of whether there is existing capacity to produce it.

Result Map Tip:

- Developing a results map is a team sport. The temptation is for one person to do it so that time is saved, but this can be ineffective in the long run.

- Time needs to be taken to develop the map. The more care taken during this phase, the easier the job of monitoring and evaluation becomes later on.

- In developing the map, focus should be on thinking through what needs to be on the ground in order to impact the lives of people. The exercise is not intended to be an academic exercise but rather one grounded in real changes that can improve people’s lives—including men, women and marginalized groups.

In developing these models, stakeholders should consider not only the contributions (interventions, programmes and outputs) of its partners and non- partners. This type of model can be extremely useful at the monitoring and evaluation stages, as it helps to capture some of the assumptions that went into designing the programmes. The draft results map is the seventh deliverable in the process.

While elaborating the results map, stakeholders should note that sometimes well intentioned actions may lead to negative results. Additionally, there may be risks that could prevent the planned results from being achieved. Therefore, it is necessary to devote time to thinking through the various assumptions, risks and possible unintended effects or outcomes.

Assumptions

Assumptions are normally defined as “the necessary and positive conditions that allow for a successful cause-and-effect relationship between different levels of results.” This means that when stakeholders think about the positive changes they would like to see and map the prerequisites for these changes, they are assuming that once those things are in place the results will be achieved. When a results map is being developed, there will always be these assumptions. The question to ask is: “If we say that having X in place should lead to Y, what are we assuming?” For example, if stakeholders say that having “high levels of public confidence and involvement in governance and decision making” should lead to “higher levels of voter turnout in elections particularly among marginalized and indigenous groups,” then stakeholders should ask, “What are we assuming?” or “Under what conditions should this happen?” Often the assumptions relate to the context within which stakeholders will work towards the desired results. In many situations, interventions are designed assuming the government will take action or allocate resources to support achievement of results. There is often a general assumption of continued social, economic and political stability within the programme’s environment.

Stating assumptions enrich programme design by identifying additional results or inputs that should be included. They also help identify risks. Assumptions may be internal or external to the organization and the particular programme. When an assumption fails to hold, results may be compromised (see Figure 8).

The assumptions that are made at the lowest levels of the results map can be expected to come true in most cases. For example, if stakeholders had stated that having “a good mass-media communication programme” and “an advocacy initiative targeted at specific stakeholders” should result in “increased awareness of women, indigenous populations, and other marginalized groups,” they may have assumed that sufficient resources would be mobilized by the partners to implement communication and awareness programmes.

A different example is a situation where the result of “high levels of public confidence and involvement in governance and decision making” was expected to lead to “higher voter turnout.” The stakeholders in this situation may have assumed that sufficient budgetary resources would be allocated to constructing voting centres and improving roads used by rural marginalized populations to get to voting centres.

It could be argued that the assumption in the first example of being able to mobilize resources for the communication and advocacy campaigns is more probable than the assumption in the second example relating to the higher level result. This is because stakeholders usually have a higher level of influence on the lower level results and assumptions.

Additional examples of assumptions include the following:

- Priorities will remain unchanged over the planning period The political roundtable agreement for bi-partisan

- Political, economic and social stability in the country or region

- Planned budget allocations to support the electoral process are actually made

- Resource mobilization targets for interventions are achieved

At this stage, stakeholders should review their results map and, for each level result, ask: “What are we assuming will happen for this result to lead to the next higher result?” The list of assumptions generated should be written on the results map.

TIP

Though stakeholders will focus most of their effort on achieving the positive result that they have developed, they must remain aware of the longer term vision and changes that they want to see. The assumptions stage is generally a good time to ask: “If we achieve the positive result we have identified, will we in fact see the longer term benefits or effects that we want?” and “What are we assuming?” In this process of thinking through the assumptions being made about the context, environment and actions that partners and non-partners should take, useful ideas may emerge that could inform advocacy and other efforts aimed at encouraging action by others.

Risks

Risks are potential events or occurrences beyond the control of the programme that could adversely affect the achievement of results. While risks are outside the direct control of the government or UNDP, steps can be taken to mitigate their effects. Risks should be assessed in terms of probability (likelihood to occur) and potential impact. Should they occur, risks may trigger the reconsideration of the overall programme and its direction. Risks are similar to assumptions in that the question stakeholders ask is: “What might happen to prevent us from achieving the results?” However, risks are not simply the negative side of an assumption. The assumption relates to a condition that should be in place for the programme to go ahead, and the probability of this condition occurring should be high. For example, in one country there could be an assumption that there will be no decrease in government spending for the programme. This should be the assumption if the stakeholders believe that the probability that there will not be a decrease is high. Risks, however, relate to the possibility of external negative events occurring that could jeopardize the success of the programme. There should be a moderate to high probability that the risks identified will occur. For example, in another country stakeholders could identify a risk of government spending being cut due to a drought, which may affect government revenue. The probability of the spending cut occurring should be moderate to high based on what is known.

Risk examples include the following:

- Ethnic tensions rise, leading to hostilities particularly against minorities

- Result of local government elections leads to withdrawal of political support for the electoral reform agenda

- Planned merger of the Department of the Interior and Office of the Prime Minister leads to deterioration of support for gender equality strategies and programmes

- Project manager leaves, leading to significant delays in project implementation (this type of risk could come during the project implementation stage)

Stakeholders should therefore again review their results map and try to identify any important risks that could affect the achievement of results. These risks should be noted beside the assumptions for each level of result.

Unintended outcomes

Programmes and projects can lead to unintended results or consequences. These are another form of risk. They are not risks that a programme’s or project’s activities will not happen, but are risks that they will happen and may lead to undesirable results.

Once the results, assumptions and risks are in place, stakeholders should discuss and document any possible unintended results or consequences. The discussion should centre around the actions that may be necessary to ensure that those unintended results do not occur. This may require other small adjustments to the results map—such as the addition of other conditions, prerequisites or interventions. It is not necessary to put the unintended results on the map itself.

Comments

Post a Comment