At this stage of the process, stakeholders should be ready to begin converting the results map into a results framework. In many situations, a smaller group of stakeholders is engaged in this undertaking. However, the wider group can participate in preparing a rough draft of the framework, using simple techniques and without going into the details and mechanics of RBM terminologies

CREATING THE DRAFT RESULT FRAMEWORK

Table 5 provides a starting point for converting the results map into a draft framework for programme and project documents. It shows how to translate some general terms and questions used in the planning session into the common programming language. The table can be used to produce an initial draft of the results framework with all or most stakeholders. It can be particularly helpful at the project level or in situations involving a diverse group of stakeholders.

FORMULATING STRONG RESULTS AND INDICATORS

Having a smaller group of persons with greater familiarity with RBM terminologies usually helps when undertaking this task. This is because it may be difficult to make progress with a large group given the technicalities involved in articulating the results framework. However, when using a smaller group, the information should be shared with the wider group for review and validation. In doing this, exercise stakeholders should:

- Use a version of Table 6.

- Refer to the guidance below on formulating the various components of the framework.

- Complete a table for each major result. Each major result (outcome) may have one or more related impacts. The expected impacts should be filled in for each major result (outcome). Likewise each outcome will have one or more outputs and so forth.

Good quality results—that is, well formulated impacts, outcomes, outputs, activities and indicators of progress—are crucial for proper monitoring and evaluation. If results are unclear and indicators are absent or poorly formulated, monitoring and evaluating progress will be challenging, making it difficult for staff and managers to know how well plans are progressing and when to take corrective actions.

The RBM terms used in this section are the harmonized terms of the UNDG, and are in line with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development- Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC) definitions.

RESULTS AND RESULTS CHAIN

The planning exercise up to this point should have led to the creation of many results and an overall results map. These results and the results map can be converted into a results chain and results framework using the standard RBM approach and terminologies.

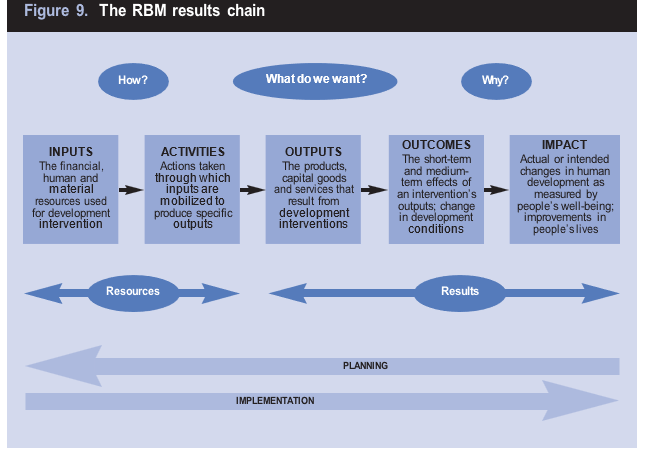

First, a ‘result’ is a defined as a describable or measurable development change resulting from a cause-and-effect relationship. Different levels of results seek to capture different development changes. The planning exercise (see Section 2.3) led to the creation of various results that were labeled as visions, effects, results, preconditions, prerequisites, interventions and so on. In the traditional RBM approach, these results are linked together into what is commonly referred to as a results chain. The results chain essentially tells us what stakeholders want to achieve, why they want to achieve it and how they will go about it. This is not very different from the results map. Now we will convert those results into more specific RBM language and begin to add performance measures to them.

As shown in the draft results framework (Table 5), the vision and longer term goals developed in the results mapping exercise are the impacts that will appear in the results framework, the immediate positive results and some of their preconditions and prerequisites will appear as outcomes, lower-level prerequisites will appear as outputs, and so on. These can be shown in the format of a results chain where the lowest level prerequisites are labeled as inputs and the highest as impacts, as illustrated in Figure 9.

FORMULATING THE IMPACT STATEMENT

Impacts are actual or intended changes in human development as measured by people’s well-being. Impacts generally capture changes in people’s lives.

The completion of activities tells us little about changes in development conditions or in the lives of people. It is the results of these activities that are significant. Impact refers to the ‘big picture’ changes being sought and represents the underlying goal of development work. In the process of planning, it is important to frame planned interventions or outputs within a context of their desired impact. Without a clear vision of what the programme or project hopes to achieve, it is difficult to clearly define results. An impact statement explains why the work is important and can inspire people to work toward a future to which their activities contribute.

Similar to outcomes, an impact statement should ideally use a verb expressed in the past tense, such as ‘improved’, ‘strengthened’, ‘increased’, ‘reversed’ or ‘reduced’. They are used in relation to the global, regional, national or local social, economic and political conditions in which people live. Impacts are normally formulated to communicate substantial and direct changes in these conditions over the long term— such as reduction in poverty and improvements in people’s health and welfare, environmental conditions or governance. The MDG and other international, regional and national indicators are generally used to track progress at the impact level.

Using the example from the results map (Section 2.3, step 5), some of the longer term impacts could be “increased public participation in national and local elections, particularly by women, indigenous populations and other traditionally marginalized groups” and “strengthened democratic processes and enhanced participation by all citizens in decisions that affect their lives.” These impacts would be part of the broader vision of a more vibrant and democratic society.

FORMULATING THE OUTCOME STATEMENT

Outcomes are actual or intended changes in development conditions that interventions are seeking to support.

Outcomes describe the intended changes in development conditions that result from the interventions of governments and other stakeholders, including international development agencies such as UNDP. They are medium-term development results created through the delivery of outputs and the contributions of various partners and non-partners. Outcomes provide a clear vision of what has changed or will change globally or in a particular region, country or community within a period of time. They normally relate to changes in institutional performance or behaviour among individuals or groups. Outcomes cannot normally be achieved by only one agency and are not under the direct control of a project manager.

Since outcomes occupy the middle ground between outputs and impact, it is possible to define outcomes with differing levels of ambition. For this reason, some documents may refer to immediate, intermediate and longer term outcomes, or short-,medium and long-term outcomes. The United Nations uses two linked outcome level results that reflect different levels of ambition:

UNDAF outcomes are the strategic, high-level results expected from UN system cooperation with government and civil society. They are highly ambitious, nearing impact-level change. UNDAF outcomes are produced by the combined effects of the lower-level, country programme outcomes. They usually require contribution by two or more agencies working closely together with their government and civil society partners.

Country programme outcomes are usually the result of programmes of cooperation or larger projects of individual agencies and their national partners. The achievement of country programme outcomes depends on the commitment and action of partners.

When formulating an outcome statement to be included in a UNDP programme document, managers and staff are encouraged to specify these outcomes at a level where UNDP and its partners (and non-partners) can have a reasonable degree of influence. In other words, if the national goals reflect changes at a national level, and the UNDAF outcomes exist as higher level and strategic development changes, then the outcomes in UNDP programme documents should reflect the comparative advantage of and be stated at a level where it is possible to show that the UNDP contribution can reasonably help influence the achievement of the outcome. For example, in a situation where UNDP is supporting the government and other stakeholders in improving the capacity of the electoral administration agency to better manage elections, outcomes should not be stated as “improved national capacities” to perform the stated functions, but rather “improved capacities of the electoral administration bodies” to do those functions. “Improved national capacity” may imply that all related government ministries and agencies have improved capacity and may even imply that this capacity is also improved within non-government bodies. If this was indeed the intention, then “improved national capacities” could be an accurate outcome. However, the general rule is that government and UNDP programme outcomes should be fairly specific in terms of what UNDP is contributing, while being broad enough to capture the efforts of other partners and non-partners working towards that specific change.

An outcome statement should ideally use a verb expressed in the past tense, such as ‘improved’, ‘strengthened’ or ‘increased’, in relation to a global, regional, national or local process or institution. An outcome should not be stated as “UNDP support provided to Y” or “technical advice provided in support of Z,” but should specify the result of UNDP efforts and that of other stakeholders for the people of that country.

- An outcome statement should avoid phrases such as “to assist/support/develop/ monitor/identify/follow up/prepare X or Y.”

- Similarly, an outcome should not describe how it will be achieved and should avoid phrases such as “improved through” or “supported by means of.”

An outcome should be measurable using indicators. It is important that the formulation of the outcome statement takes into account the need to measure progress in relation to the outcome and to verify when it has been achieved. The outcome should therefore be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time- bound (SMART). The following illustrate different levels of outcomes:

- Policy, legal and regulatory framework reformed to substantially expand connectivity to information and communication technologies (short to medium term)

- Increased access of the poor to financial products and services in rural communities (medium to long term)

- Reduction in the level of domestic violence against women in five provinces by 2014 (medium to long term)

- Increased volume of regional and subregional trade by 2015 (medium to long term)

Using the previous elections example, the outcome at the country programme level may be “enhanced electoral management systems and processes to support free and fair elections” or “electoral administrative policies and systems reformed to ensure freer and fairer elections and to facilitate participation by marginalized groups.”

FORMULATING THE OUTPUT STATEMENT

Since outputs are the most immediate results of programme or project activities, they are usually within the greatest control of the manager. It is important to define outputs that are likely to make a significant contribution to the achievement of the outcomes.

In formulating outputs, the following questions should be addressed:

n What kind of policies, guidelines, agreements, products and services do we need in order to achieve a given outcome?

- Are they attainable and within our direct control?

- Do these outputs reflect an appropriate strategy for attaining the outcome? Is there a proper cause and effect relationship?

- Do we need any additional outputs to mitigate potential risks that may prevent us from reaching the outcome?

- Is the output SMART—specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound?

It is important to bear in mind:

- Outputs must be deliverable within the respective programming cycle.

- Typically, more than one output is needed to obtain an outcome.

- If the result is mostly beyond the control or influence of the programme or project, it cannot be output.

Outputs generally include a noun qualified by a verb describing positive change. For example:

- Study of environment-poverty linkages completed

- Police forces and judiciary trained in understanding gender violence

- National, participatory forum convened to discuss draft national anti-poverty strategy

- National human development report produced and disseminated

Returning to our example, there could be a number of outputs related to the outcome “electoral management policies and systems reformed to ensure freer and fairer elections and to facilitate participation by marginalized groups.” Outputs could include:

- Advocacy campaign aimed at building consensus on need for electoral law and system reform developed and implemented

- Systems and procedures implemented and competencies developed in the national electoral management agency to administer free and fair elections

- Training programthe me on use of new electoral management technology designed

- and implemented for staff of electoral management authority

- Revised draft legislation on the rights of women and indigenous populations to participate in elections prepared

- Electoral dispute resolution mechanism established

FORMULATING THE ACTIVITIES

Activities describe the actions that are needed to obtain the stated outputs. They are the coordination, technical assistance and training tasks organized and executed by project personnel.

In an RBM context, carrying out or completing a programme or project activity does not constitute a development result. Activities relates to the processes involved in generating tangible goods and services or outputs, which in turn contribute to outcomes and impacts.

In formulating activities, the following questions should be addressed:

- What actions are needed in order to obtain the output?

- Will the combined number of actions ensure that the output is produced?

- What resources (inputs) are necessary to undertake these activities?

It is important to bear in mind:

- Activities usually provide quantitative information and they may indicate periodic- ity of the action.

- Typically, more than one activity is needed to achieve an output.

Activities generally start with a verb and describe an activity or action. Using our example, activities could include:

- Provide technical assistance by experts in the area of electoral law reform

- Develop and deliver training and professional development programmes for staff

- Organize workshops and seminars on electoral awareness

- Publish newsletters and pamphlets on electoral rights of women and minorities

- Procure equipment and supplies for Electoral Management Authority

- Engage consultants to draft revised electoral laws

FORMULATING INPUTS

Inputs are essentially the things that must be put in or invested in order for activities to take place.

Though not dealt with in detail in this manual, inputs are also part of the results chain. Inputs include the time of staff, stakeholders and volunteers; money; consultants; equipment; technology; and materials. The general tendency is to use money as the main input, as it covers the cost of consultants, staff, materials, and so forth. However, in the early stages of planning, effort should be spent on identifying the various resources needed before converting them into monetary terms.

The guidance above should help to prepare the first column (‘results’) in the results framework.

FORMULATING PERFORMANCE INDICATORS

Indicators are signposts of change along the path to development. They describe the way to track intended results and are critical for monitoring and evaluation.

Good performance indicators are a critical part of the results framework. In particular, indicators can help to:

- Inform decision making for ongoing programme or project management

- Measure progress and achievements, as understood by the different stakeholders

- Clarify consistency between activities, outputs, outcomes and impacts

- Ensure legitimacy and accountability to all stakeholders by demonstrating progress

- Assess project and staff performance

Indicators may be used at any point along the results chain of activities, outputs, outcomes and impacts but must always directly relate to the result being measured. Some important points include the following:

- Who sets indicators is fundamental, not only to ownership and transparency but also to the effectiveness of the indicators. Setting objectives and indicators should be a participatory process.

- A variety of indicator types is more likely to be effective. The demand for objective verification may mean that focus is given to the quantitative or simplistic at the expense of indicators that are harder to verify but may better capture the essence of the change taking place.

- The fewer indicators, the better. Measuring change is costly, so use as few indicators as possible. However, there must be indicators in sufficient numbers to measure the breadth of changes happening and to provide cross-checking.

The process of formulating indicators should begin with the following questions:

- How can we measure that the expected results are being achieved?

- What type of information can demonstrate a positive change?

- What can be feasibly monitored with given resource and capacity constraints?

- Will timely information be available for the different monitoring exercises?

- What will the system of data collection be, and who will be responsible?

- Can national systems be used or augmented?

- Can government indicators be used?

Quantitative and qualitative indicators

Indicators can either be quantitative or qualitative. Quantitative indicators are statistical measures that measure results in terms of:

- Number

- Percentage

- Rate (example: birth rate—births per 1,000 population)

- Ratio (example: sex ratio—number of males per number of females)

Qualitative indicators reflect people’s judgements, opinions, perceptions and attitudes towards a given situation or subject. They can include changes in sensitivity, satisfaction, influence, awareness, understanding, attitudes, quality, perception, dialogue or sense of well-being.

Qualitative indicators measure results in terms of:

- Compliance with…

- Quality of…

- Extent of…

- Level of …

Note that in the example used in Box 13 on the commitment of government partners, sub indicators are being used to assess the quality of the strategy, “Did it benefit from the involvement of other stakeholders?”; the extent of senior management engagement; and the level of commitment, “Is there also a budget in place?”

As far as possible, indicators should be disaggregated. Averages tend to hide disparities, and recognizing disparities is essential for programming to address the special needs of groups such as women, indigenous groups and marginalized populations. Indicators can be disaggregated by sex, age, geographic area and ethnicity, among other things.

The key to good indicators is credibility—not volume of data or precision in measurement. Large volumes of data can confuse rather than bring focus and a quantitative observation is no more inherently objective than a qualitative observation. An indicator’s suitability depends on how it relates to the result it intends to describe.

Proxy indicators

Sometimes, data will not be available for the most suitable indicators of a particular result. In these situations, stakeholders should use proxy indicators. Proxy indicators are a less direct way of measuring progress against a result. For example, take the outcome: “improved capacity of local government authorities to deliver solid waste management services effectively and efficiently.” Some possible direct indicators could include:

- Hours of down time (out-of-service time) of solid waste vehicle fleet due to maintenance and other problems

- Percentage change in number of households serviced weekly

- Percentage change in number of commercial properties serviced weekly

- Percentage of on-time pick-ups of solid waste matter in [specify] region within last six-month period

Assuming no system is in place to track these indicators, a possible proxy or indirect indicator could be: A survey question capturing the percentage of clients satisfied with the quality and timeliness of services provided by the solid waste management service. (The agency may find it easier to undertake a survey than to introduce the systems to capture data for the more direct indicators.)

The assumption is that if client surveys show increased satisfaction, then it may be reasonable to assume some service improvements. However, this may not be the case, which is why the indicator is seen as a proxy rather than a direct measure of the improvement.

Similarly, in the absence of reliable data on corruption in countries, many development agencies use the information from surveys that capture the perception of corruption by many national and international actors as a proxy indicator.

In the Human Development Index, UNDP and other UN organizations use ‘life expectancy' as a proxy indicator for health care and living conditions. The assumption is that if people live longer, then it is reasonable to assume that health care and living conditions have improved. Real gross domestic product/capita (purchasing power parity) is also used in the same indicator as a proxy indicator for disposable income.

Levels of indicators

Different types of indicators are required to assess progress towards results. Within the RBM framework, UNDP uses three types of indicators:

- Impact indicators

- Outcome indicators

- Output indicators

Impact indicators describe the changes in people’s lives and development conditions at global, regional and national levels. In the case of community-level initiatives, impact indicators can describe such changes at the subnational and community levels. They provide a broad picture of whether the development changes that matter to people and UNDP are actually occurring. In the context of country-level planning (CPD), impact indicators are often at the UNDAF and MDG levels, and often appear in the UNDAF results framework. Impact indicators are most relevant to global, regional and national stakeholders and senior members of the UNCT for use in monitoring. Table 8 includes some examples of impact indicators.

Outcome indicators assess progress against specified outcomes. They help verify that the intended positive change in the development situation has actually taken place. Outcome indicators are designed within the results framework of global, regional and country programmes. Outcome indicators are most often useful to the UN organization and its partners working on the specific outcome. Table 9 gives a few examples.

In the second example in Table 9, an indicator of whether policies are being changed is used together with one on the number of people with access to the Internet to give a broad and complementary view of overall progress against the outcome. It is often necessary to use a set of complementary indicators to measure changes attributable to reasons other than the intervention in question. Also, composite indicators can be used to provide more qualitative measures of progress. Stakeholders can agree on their own composite indicators in areas where no good composite indicator already exists.

Output indicators assess progress against specified outputs. Since outputs are tangible and deliverable, their indicators may be easier to identify. In fact, the output itself may be measurable and serve as its own indication of whether or not it has been produced. Table 10 includes some examples.

Baselines and targets

Once the indicators are identified, the stakeholders should establish baselines and targets for the level of change they would like to see. It is often better to have a small group undertake the effort of researching the baseline separately, as stakeholders may not have all the data at the time. The baseline and target should be clearly aligned with the indicator, using the same unit of measurement. (For practical reasons, some indica- tors may need to be adjusted to align with existing measures, such as national surveys or censuses.)

Baseline data establishes a foundation to measure change. Without baseline data, it is very difficult to measure change over time or to monitor and evaluate. With baseline data, progress can be measured against the situation that prevailed before an intervention.

Ideally, the baseline should be gathered and agreed upon by stakeholders when a programme is being formulated. However for some ongoing activities, baseline data may not have been established at that time. In this case, it may be possible to approximate the situation when the programme started by using data included in past annual review exercises. If this data does not exist, it still may be possible to obtain a measure of change over time. For example, to establish a baseline pertaining to the local governance, one might conduct a survey and ask: “Compared to three years ago, do you feel more or less involved in local decision-making?” When it is impossible to retroactively establish any sense of change, establish a measure of what the situation is now. This will at least allow for the assessment of change in the future. In some situations, a new indicator may be created, and this may not have a baseline from a previous year. In this situation and other situations, the team can agree to develop the baseline as they move forward with implementing the programme.

Once the baseline is established, a target should be set. The target will normally depend on the programme period and the duration of the interventions and activities. For example, within the context of a UNDAF, targets are normally set as five-year targets so as to correspond with the duration of the UNDAF. Likewise, global, regional, and country programmes will normally have four- to five-year targets. While some development changes can take a long time to occur, often 10 years or more, the inclusion of a target for the programme or project cycle is intended to enable stakeholders to look for ‘signs’ of overall change. If targets cannot be set for a four- to five-year period, then the indicator used was probably too high a level, and the team will need to find other indicators of progress within the short to medium term.

At the output level, targets can be set for a much shorter period, such as one year, six months and so forth. Relating this to our indicator examples above, Table 11 gives examples of baselines and targets.

It may not always be possible to have a strong or high output indicator target for the first year of implementation. For example, consider the indicator in Table 10: “percentage of electoral management office staff and volunteers trained in techniques to reduce voter fraud.” A number of actions may need to be taken in the first year before training begins in the second year. The target for this indicator could therefore be 0 percent in 2009. This does not mean that the indicator is weak. In situations like this, a ‘comments’ field could be used to explain the target. This is another reason why having two or more indicators to capture different output dimensions is recommended (the same applies to the outcome). In this case, another indicator on “level of progress made” in putting in place basic systems, training materials and so forth could be used in addition to the numeric indicator. This would allow for qualitative targets to be set for each year and could address the things that are to be put in place to form the platform for activities that will occur in future years.

Means of verification

Results statements and indicators should be SMART. The ‘M’ in SMART stands for ‘measurable’, which implies that data should be readily available in order to ascertain the progress made in achieving results. In defining results and corresponding indicators, it is thus important to consider how data will be obtained through monitoring and evaluation processes.

Means of verification play a key role in grounding an initiative in the realities of a particular setting. Plans that are too ambitious or developed too hastily often fail to recognize the difficulties in obtaining evidence that will allow programme managers to demonstrate the success of an initiative. Without clearly defining the kind of evidence that will be required to ascertain the achievement of results, without fully considering the implications of obtaining such evidence in terms of effort and cost, planners put the integrity of the programme at risk. If results and indicators are not based on measurable, independently verifiable data, the extent to which an initiative is realistic or achievable is questionable.

Identifying means of verification should take place in close coordination with key stakeholders. Evidence on outcomes (let alone impact) will need to be provided by the target group, beneficiaries or development partners. Therefore, it is important that in planning programmes and projects, such stakeholders are involved in thinking about how evidence on progress will be obtained during implementation and after comple- tion of the initiative. Clear means of verification thus facilitates the establishment of monitoring systems and contributes significantly to ensuring that programmes and projects are evaluation-ready.

Based on this guidance, the team of stakeholders should refine or finalize the results framework for either the programme or project being developed.

The formulation of a results framework is a participatory and iterative process. Participation is key to ensuring that stakeholders understand and support the initiative and are aware of the implications of all elements of the results framework. In develop- ing a results framework, the definition of new elements (such as formulating outputs after identifying outcomes, or defining indicators after defining a particular result, or specifying the means of verification after defining indicators) should be used to test the validity of previously defined elements.

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE RESULTS FRAMEWORK AND UNDP RBM SYSTEMS

The data created in the planning exercise may appear at different times in various planning documents and systems. For example:

- The impacts and/or national priorities appear in the relevant sections of the UNDAF or global, regional or country programme results framework when these are developed.

- The impact developed in a global, regional or country programme would also be entered in the RBM platform (home.undp.org) in the global, regional or national goal field.

- Impact indicators are normally entered in national strategy documents and plans and in the UNDAF results framework. Reference can also be made to these indicators in the situation analysis and statements of objective in a CPD or CPAP.

- The analysis of what is causing the problems would normally be reflected in the situation analysis section of the respective programme or project document.

- The analysis of what needs to happen or be in place to achieve the goals and impact would also be reflected in the programme or project document, along with any government or UNDP action needed to influence partners and non-partners to take desired actions. This would be captured in the objectives and strategy sections of the respective documents.

- The specific outcomes that UNDP will support would be entered in the relevant sections of the UNDAF.

- The UNDP outcomes identified in the UNDAF are used to formulate the CPD that is approved by the UNDP Executive Board.

- The same outcomes (or slightly revised outcomes based on the CPAP process but with the same intention) would be entered into Atlas as part of the programme’s project tree. These outcomes would then appear on the programme planning and monitoring page of the RBM platform.

- Outcome indicators would be entered in the relevant sections of the programme documents and the same indicators (or slightly revised indicators based on the CPAP refinement process) would be entered into the RBM platform at the start of the programme.

- Baselines and targets would be entered for the outcome indicators in both places as well.

In the UNDAF, all the relevant indicators for the UNDAF outcomes would also be included, along with the outputs of the different UN organizations contributing to those outcomes. Likewise, the national priorities would have their related indicators and outputs in the government’s development strategies. UNDP staff (both programme and operations) should be familiar with these higher level results and performance targets in order to better manage for results in their own programmes and projects.

In UNDP and many other agencies, the information obtained from the planning process is normally used to develop not only the results framework but also a narrative programme or project document. This document may have requirements that go beyond the issues dealt with in this Handbook. Users of the Handbook should therefore consult with their respective agency policies and procedures manuals for guidance.

Comments

Post a Comment